Private Life: Letters from Annie Gray

Below are two letters, one of which contained a newspaper clipping, from Annie A. Gray to Eartha M. M. White, written eleven years apart. Connections can be made between people Annie mentions and the Free African Society, as well as other Black churches in Jacksonville, FL and Washington, D.C.

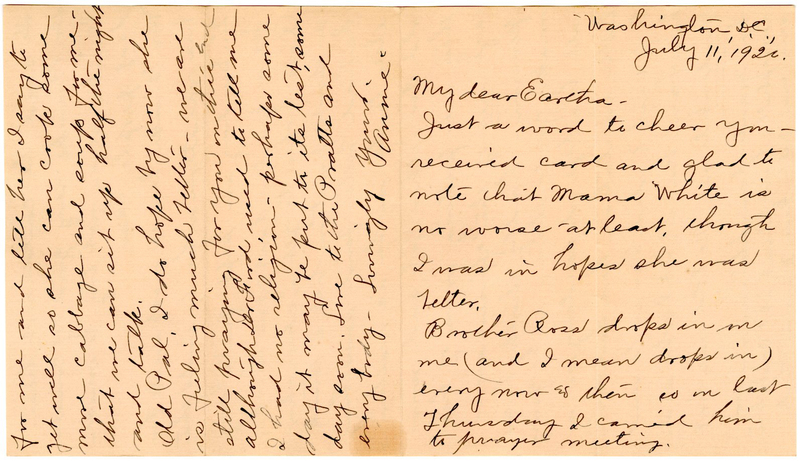

July 11, 1920: Annie mentions taking a friend with her to "prayer meeting" and her friend complains of being unable to hear "Dr. Grimké". According to Jennifer Bibb, Special Collections Coordinator at the University of North Florida, this is most likely a reference to Francis J. Grimké, a Presbyterian minister who served in Washington D.C. and Jacksonville, FL. Francis Grimké was born in Charleston, South Carolina on November 4th, 1850 to a white planter named Henry Grimké and an enslaved Black woman, Nancy Weston Grimké. Francis passed into the guardianship of an older half-brother who sold Francis to a Confederate officer and Francis endured enslavement until the end of the Civil War. While then attending school in Charleston, Francis was noticed by abolitionist Frances Pillsbury who sponsored his education at Lincoln University; Francis graduated as the valedictorian (and was later awarded a doctorate in Divinity). Francis then studied at Princeton Theological Seminary and chose a calling as a Presbyterian minister. He served at Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church in Washington D.C., except during 1885-1889 when he served at Laura Street Presbyterian Church in Jacksonville, Florida (Weeks 473-474). Interestingly, Francis wrote an effusive introduction to Recollections of Seventy Years, Bishop Daniel Alexander Payne’s memoir; the same man who sent Reverend Charles H. Pearce to Florida, an action which resulted in the founding of Edward Waters College.

Annie mentions that Dr. Grimké will soon be taking a vacation, one that she says is "quite long for a pastor, don't you think?" Annie also mentions that her and Eartha's mutual acquaintance, Brother Ross, would like a church position. Annie seems skeptical of that idea (to say the least) but it does indicate that churches served as places of employment as well as houses of worship. Annie also mentions "Dr. Ford", a likely reference to John E. Ford, pastor at Bethel Baptist Institutional Church in Jacksonville, Florida. The origin of Annie and Eartha's relationship is currently unclear, but this letter suggests that they at least knew one another from a network of church members. So, in addition to worship and employment, churches served as a means to friendship.

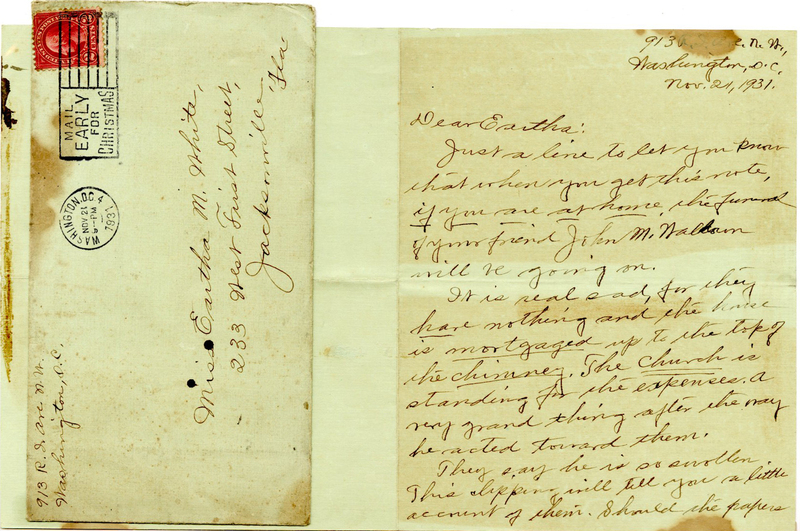

November 21, 1931: Annie reports the upcoming funeral of a mutual acquaintance, Reverend John Milton Waldron, and Mrs. Waldron’s subsequent heartache. Annie mentions the Waldron’s mortgage debt and that “the church is standing for the expenses.” It is not clear which church or which expenses (perhaps the mortgage or the funeral). This is an "example of how the Negro church has had to function as a substitute for meeting needs which among people otherwise circumstanced would be supplied by various agencies” (Journal of Negro History 460). Though the church was financially aiding Waldron's family, Annie’s letter suggests that Reverend Waldron had a troubled relationship with that church or its members. Included in Annie’s letter to Eartha is a newspaper clipping of Reverend Waldron’s obituary (see item below).

Annie also mentions Reverend Walter Brooks: considering information found in the Journal of Negro History and African American Lives (co-edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.), this is a possible reference to Walter Henderson Brooks who served as pastor at Nineteenth Street Baptist Church in Washington, D.C. from 1882 to 1945. Like Francis Grimké, Reverend Brooks attended Lincoln University (possibly at the same time) and was acquainted with Francis' brother, Archibald (Journal of Negro History 459). In this letter, Annie writes that Reverend Brooks will be burying his wife the day before Reverend Waldron’s funeral. It is likely that Annie is referencing Florence H. Swann, Reverend Brooks’ second wife whom he married in 1915 (Journal of Negro History 461).

Like Reverend Grimké, Reverend Waldron also served in Washington D.C. and Jacksonville, Florida. Although, Reverend Waldron was almost fifteen years younger and was only just graduating from seminary when Reverend Grimké was returning to Washington D.C. from his four year pastorate at Laura Street Presbyterian Church. As one might expect, since the paper in which this obituary was printed (The Evening Star) was based in Washington D.C., the article does not expand on Reverend Waldron’s service in Florida. However, an entry in the Jane Addams Digital Collection does include information about Reverend Waldron’s active pastorate in Jacksonville: In 1892 (the same year Edward Waters College was founded), he joined Bethel Baptist Church. After the church burned in 1901 (perhaps, like Edward Waters College, as a consequence of the Great Fire of Jacksonville), Reverend Waldron established the first Black institutional church “which worked in a similar fashion as settlement houses, offering various things such as vocational training, athletics, sewing courses, and recreation.” While in Florida, Reverend Waldron practiced civil rights activism and founded the Afro-American Industrial Insurance Society. In 1906, Reverend Waldron returned to Washington D.C. where, according to the obituary, he established another institutional church and remained active in matters of community improvement. He was buried at Harmony Cemetery, a burial ground originally maintained by the Columbian Harmony Society which is another example of a benevolent society meant to aid Black citizens (Richardson, 307). Reverend Waldron’s life history reveals that pastors engaged in spiritual, social, and political matters. Even 150 years later, Black churches and their congregations carried on the legacy of the Free African Society.